The Mabey Logistic Support Bridge (in the United States, the Mabey-Johnson Bridge) is a portable pre-fabricatedtruss bridge, designed for use by military engineering units to upgrade routes for heavier traffic, replace civilian bridges damaged by enemy action or floods etc., replace assault and general support bridges and to provide a long span floating bridge capability.[1] The bridge is a variant of the Mabey Compact 200 bridge, with alterations made to suit the military user as well as a ramp system to provide ground clearance to civilian and military vehicles.

Description[edit]

Mabey’s Panel Bridge Systems Mabey rents and sells a wide-range of prefabricated, modular bridging systems to meet most temporary or permanent needs. Across the country and around the world, engineers, contractors, and municipalities turn to Mabey for access solutions. The panel bridge systems are manufactured to. #baileybridge The Bailey bridge is a type of portable, pre-fabricated, truss bridge. It was developed by the British during World War II for military use and saw extensive use by British, Canadian. Bridge jacked up off the rollers and lowered onto its permanent bearings on the abutments. No piling will be done, as the foundations will be on spread footing. The abutments. Mabey & Johnson Priority Bridges Programme National Works Agency # # -.1.

The Logistic Support Bridge is a non-assault bridge for the movement of supplies and the re-opening of communications. It is a low-cost system that can be used widely throughout the support area, as well as for a range of defined applications. All types of vehicles including civilian vehicles with low ground clearances are accommodated.[1]

The Mabey Logistic Support Bridge originated from the Bailey bridge concept. Compared with World War II material in use throughout the world, LSB is manufactured with chosen modern steel grades, with a strong steel deck system. With strong deep transoms, there are only two per bay instead of the four previously needed on Bailey bridges.[citation needed]

Beyond the need for the re-opening of communications, Logistic Support Bridge-based equipment (Compact 200) can be used as a rescue bridge for relief in natural disaster situations or as a civilian bridge for semi-permanent bridging to open up communications in some of the most remote regions of the world.

Users[edit]

The bridge is manufactured by Mabey Group at its Mabey Bridge factory in Lydney, Gloucestershire (Mabey Group's original factory, now closed, was in Chepstow and manufactured large bridge girders; in May 2019, the Group sold Mabey Bridge to the US-based Acrow Bridge).[2]

The name LSB was given by the British Army (Royal Engineers) to supply bridging to satisfy their specific requirements for a logistic or line of communication bridging. The LSB went into service with the British Army on 21 December 2001. The system is proved and approved by a number of NATO forces.

Armies from a number of countries around the world own equipment or have trained and deployed on the system, notably during the crisis in the Balkans. These Armies include Argentina, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Bulgaria, Cambodia, Canada, Chile, Denmark, Ecuador, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Malaysia, Nepal, Netherlands, Romania, Sri Lanka, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Tanzania, Turkey, Venezuela, United Kingdom, United States.

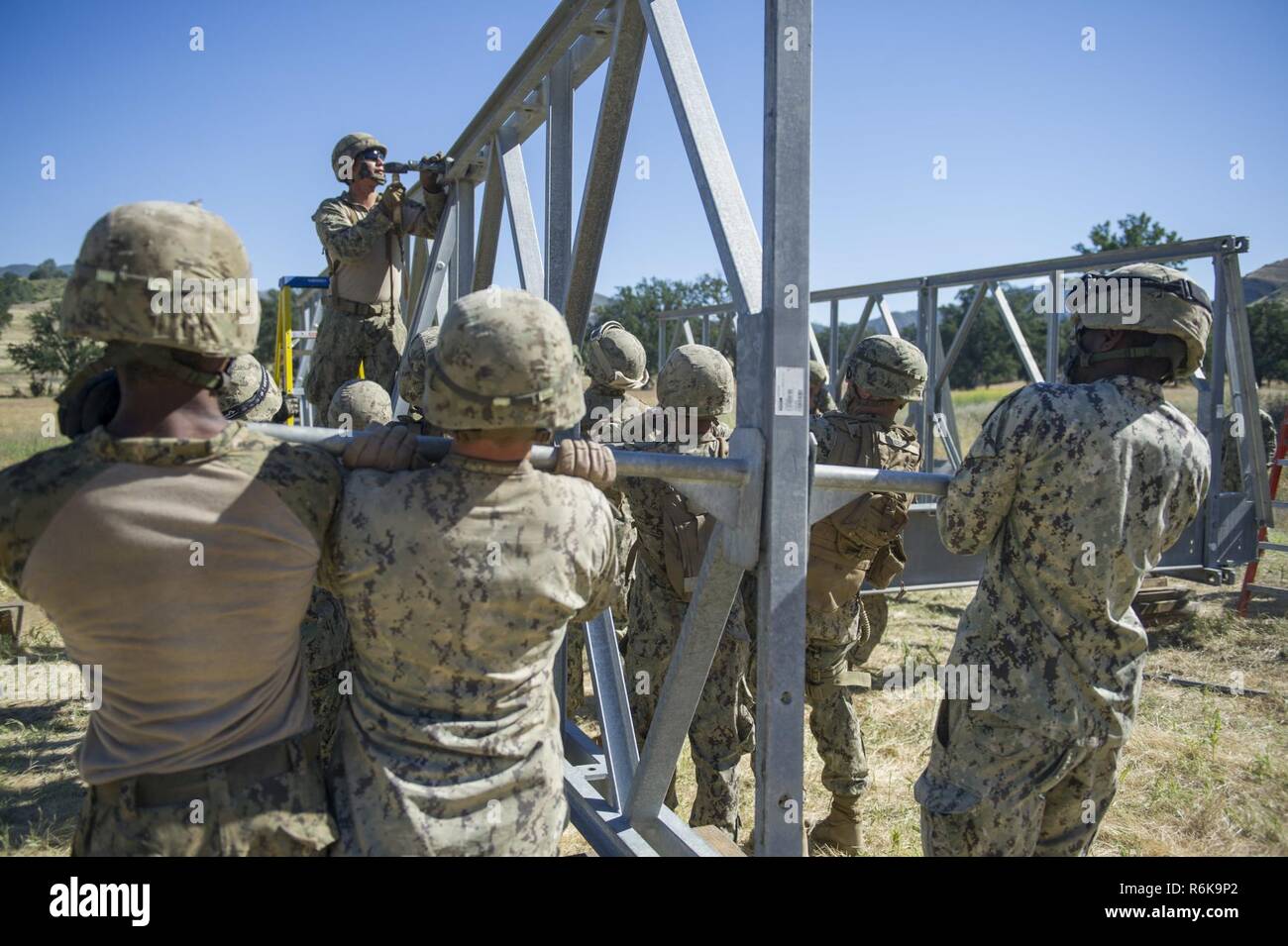

The bridge has been built in many locations across Iraq and Afghanistan by the U.S. Naval Mobile Construction Battalions (Seabees) and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.During the Canadian OPERATION ATHENA, members of 1 CER on Task Force 3-09 constructed a Mabey Logistic Support Bridge over a pre-existing bridge after a vehicle borne suicide bomb detonated on the bridge close to Kandahar Airfield

The Swedish Transport Administration also uses the bridge where it is used during road renovation and construction or as a stop gap after road damage.[3]

Features[edit]

- The bridge takes military load class 80 Tracked, 110 Wheeled

- The bridge can span up to 61m

- LSB has a lane width of 4.2m

- Multi-span equipment enables the bridge to be built to any length on fixed or floating supports

- Built on a greenfield site using grillages, ground beams and ramps

- The bridge is normally built using an atc244 22 ton capacity crane or a hydraulic excavator using a bucket with a lifting eye.

System description[edit]

The LSB combines standard off the shelf equipment with a range of purpose designed special equipment to meet the expectations of modern military loads and traffic expectations.

- Panels —These are the main structural components of the bridge trusses. They are welded items comprising top and bottom chords interconnected by vertical and diagonal bracing. At the end of each panel, chords terminate in male lugs or eyes and at the other end in female lugs or eyes. This allows panels to be pinned together to form the bridge span. There are two different panels; a Super Panel and a High Shear Super Panel. The High Shear Super Panel is used at each end of the bridge span depending upon the loading criteria.

- Chord reinforcement —These are constructed in the same way as the chords of the bridge panels and are bolted to the panels to increase the bending capacity of the bridge. For the LSB a heavy chord reinforcement is used.

- Transoms —These are fabricated from universal beams and form the cross girders of the bridge, spanning between the panels and carrying the bridge deck. The transom is designed for the appropriate loading criteria and for LSB is designed to accommodate MLC80T/110W.

- Decks —Unlike wooden Bailey decks, the steel LSB decks are 1.05m x 3.05m and are manufactured using robotic welding technology. The decks are manufactured to have a long fatigue life and with durbar/checkered plate finish. The decks withstand both wheeled and tracked vehicles.

- Bracing —A variety of bracing members are used to connect panels to form the bridge trusses and to brace adjacent transoms to the bridge.

- Grillages and Ground Beams —On greenfield sites and when being used as an over bridge, ground beams are available that form an assembly which transmits all dead and live forces from the bridge into the ground. For a 40m (MLC80T/110W) bridge the ground bearing pressure is 200 kN/m2. The grillages are located on the top of the ground beams and accommodate the bridge bearings as well as the head of the ramp transom.

- Ramps —The slope or profile of the ramps can be adjusted to allow for the passage of a range of civilian and military traffic. The length of a standard ramp at each end of the bridge is 13.5m. The ramps are bolted to the grillages and use standard deck units supported on special transoms. These transoms can be positioned at a variety of heights depending upon the set adopted with a special ramp post. The interface between the ramp and ground is a special toe ramp unit (1.5m)

Construction[edit]

The bridge can be constructed by the cantilever launch method without the need for any temporary intermediate support. This is achieved by erecting a temporary launching nose at the front of the bridge and pushing the bridge over the gap on rollers.

After pushing the bridge over the gap, the launching nose is dismantled and the bridge is jacked down onto its bearings. The launching nose is largely constructed from standard bridge components.

Floating variants[edit]

There are a number of floating versions of the Mabey LSB in use across Iraq: Floating Piers which consist of steel Flexifloat pontoon units, Landing Piers consisting of 16 pontoon units, and Intermediate Piers which consist of 8 pontoons each. Hand winches are mounted on steel trays which are bolted to the pontoons. The anchors are connected to the hand winches and pontoons via steel chain and polypropylene ropes. Special span junction decks allow for the rotation of the floating spans as the spans deflect under live load.

If the bridge is relatively short in terms of the number of spans, it may be possible to launch the complete bridge from one bank. On a long span bridge, launching intermediate spans and floating them into position on intermediate piers is more practical.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ abMabey & Johnson. 'Logistic Support Bridge'. M&J UK website. Retrieved 10 December 2009.

- ^'Acrow buys Mabey Bridge'. The Construction Index. 13 May 2019. Retrieved 13 May 2019.

- ^http://www.forsvarsmakten.se/sv/aktuellt/2017/09/varselgult-och-gront-samarbete-i-orsundsbro/

External links[edit]

Maybe Johnson Bridge Ppt

| Related | Callender-Hamilton bridge |

|---|---|

| Descendant | Mabey Logistic Support Bridge, Medium Girder Bridge |

| Carries | Pedestrians, Road vehicles, Rail Vehicles |

| Span range | Short |

| Material | Timber, steel |

| Movable | No |

| Design effort | Low |

| Falsework required | None |

A Bailey bridge is a type of portable, pre-fabricated, trussbridge. It was developed in 1940-1941 by the British for military use during the Second World War and saw extensive use by British, Canadian and US military engineering units. A Bailey bridge has the advantages of requiring no special tools or heavy equipment to assemble. The wood and steel bridge elements were small and light enough to be carried in trucks and lifted into place by hand, without requiring the use of a crane. The bridges were strong enough to carry tanks. Bailey bridges continue to be used extensively in civil engineering construction projects and to provide temporary crossings for foot and vehicle traffic.

- 2History

Design[edit]

The success of the Bailey bridge was due to the simplicity of the fabrication and assembly of its modular components, combined with the ability to erect and deploy sections with a minimum of assistance from heavy equipment. Many previous designs for military bridges required cranes to lift the pre-assembled bridge and lower it into place. The Bailey parts were made of standard steelalloys, and were simple enough that parts made at a number of different factories could be completely interchangeable. Each individual part could be carried by a small number of men, enabling army engineers to move more easily and more quickly than before, in preparing the way for troops and matériel advancing behind them. Finally, the modular design allowed engineers to build each bridge to be as long and as strong as needed, doubling or tripling up on the supportive side panels, or on the roadbed sections.[1]

The basic bridge consists of three main parts. The bridge's strength is provided by the panels on the sides. The panels are 10-foot-long (3.0 m), 5-foot-high (1.5 m), cross-braced rectangles that each weigh 570 pounds (260 kg), and can be lifted by six men. The panel was constructed of welded steel. The top and bottom chord of each panel had interlocking male and female lugs into which engineers could inset panel connecting pins.[2]

The floor of the bridge consists of a number of 19-foot-wide (5.8 m) transoms that run across the bridge, with 10-foot-long (3.0 m) stringers running between them on the bottom, forming a square.[3] Transoms rest on the lower chord of the panels, and clamps hold them together. Stringers are placed on top of the completed structural frame, and wood planking is placed on top of the stringers to provide a roadbed. Ribands bolt the planking to the stringers. Later in the war, the wooden planking was covered by steel plates, which were more resistant to the damage caused by tank tracks.

Each unit constructed in this fashion creates a single 10-foot-long (3.0 m) section of bridge, with a 12-foot-wide (3.7 m) roadbed. After one section is complete it is typically pushed forward over rollers on the bridgehead, and another section built behind it. The two are then connected together with pins pounded into holes in the corners of the panels.

For added strength several panels (and transoms) can be bolted on either side of the bridge, up to three. Another solution is to stack the panels vertically. With three panels across and two high, the Bailey Bridge can support tanks over a 200-foot span (61 m). Footways can be installed on the outside of the side-panels; the side-panels form an effective barrier between foot and vehicle traffic and allow pedestrians to safely use the bridge.[4]

A useful feature of the Bailey bridge is its ability to be launched from one side of a gap.[3] In this system the front-most portion of the bridge is angled up with wedges into a 'launching nose' and most of the bridge is left without the roadbed and ribands. The bridge is placed on rollers and simply pushed across the gap, using manpower or a truck or tracked vehicle, at which point the roller is removed (with the help of jacks) and the ribands and roadbed installed, along with any additional panels and transoms that might be needed.

During the Second World War, Bailey bridge parts were made by companies with little experience of this kind of engineering. Although the parts were simple, they had to be precisely manufactured if they were fit each other correctly, so they were assembled into a test bridge at the factory to make sure of this. To do this efficiently, newly manufactured parts would be continuously added to the test bridge, while at the same time the far end of the test bridge was continuously dismantled and the parts dispatched to the end-users.[4]

History[edit]

Donald Bailey was a civil servant in the BritishWar Office who tinkered with model bridges as a hobby.[5] He had proposed an early prototype for a Bailey bridge before the war in 1936,[6] but the idea was not acted upon.[7] Bailey drew an original proposal for the bridge on the back of an envelope in 1940.[5][8] On 14 February 1941, the Ministry of Supply requested that Bailey have a full-scale prototype completed by 1 May.[9] Work on the bridge was completed with particular support from Ralph Freeman.[10] The design was tested at the Experimental Bridging Establishment (EBE), in Christchurch, Hampshire,[7][11] with several parts from Braithwaite & Co.,[12] beginning in December 1940 and ending in 1941.[7][11] The first prototype was tested in 1941.[13] For early tests, the bridge was laid across a field, about 2 feet (0.61 m) above the ground, and several Mark V tanks were filled with pig iron and stacked upon each other.[12]

The prototype of this was used to span Mother Siller's Channel, which cuts through the nearby Stanpit Marshes, an area of marshland at the confluence of the River Avon and the River Stour. It remains there (50°43′31″N1°45′44″W / 50.7252806°N 1.762155°W) as a functioning bridge.[14] Full production began in July 1941. Thousands of workers and over 650 firms, including Littlewoods, were engaged in making the bridge, with production eventually rising to 25,000 bridge panels a month.[15] The first Bailey bridges were in military service by December 1941,[13] Bridges in the other formats were built, temporarily, to cross the Avon and Stour in the meadows nearby. After successful development and testing, the bridge was taken into service by the Corps of Royal Engineers and first used in North Africa in 1942.[16]

The original design violated a patent on the Callender-Hamilton bridge. The designer of that bridge, A. M. Hamilton, successfully applied to the Royal Commission on Awards to Inventors. The Bailey Bridge was more easily constructed, but less portable than the Hamilton bridge.[17][18] Hamilton was awarded £4,000 in 1936 by the War Office for the use of his early bridges and the Royal Commission on Awards to Inventors awarded him £10,000 in 1954 for the use, mainly in Asia, of his later bridges. Lieutenant GeneralSirGiffard Le Quesne Martel was awarded £500 for infringement on the design of his box girder bridge, the Martel bridge.[19] Bailey was later knighted for his invention, and awarded £12,000.[20][21]

Use in the Second World War[edit]

The first operational Bailey bridge during the Second World War was built by 237 Field Company R.E. over Medjerda River near Medjez el Bab in Tunisia on the night of 26 November 1942.[22] The first of a Bailey bridge built under fire was at Leonforte by members of the 3rd Field Company, Royal Canadian Engineers.[23][unreliable source?] The Americans soon adopted the Bailey bridge technique, calling it the Portable Panel Bridge. In early 1942, the United States Army Corps of Engineers initially awarded contracts to the Detroit Steel Products Company, the American Elevator Company and the Commercial Shearing and Stamping Company, and later several others.[24]

The Bailey provided a solution to the problem of German and Italian armies destroying bridges as they retreated. By the end of the war, the US Fifth Army and British 8th Army had built over 3,000 Bailey bridges in Sicily and Italy alone, totaling over 55 miles (89 km) of bridge, at an average length of 100 feet (30 m). One Bailey, built to replace the Sangro River bridge in Italy, spanned 1,126 feet (343 m). Another on the Chindwin River in Burma, spanned 1,154 feet (352 m).[25] Such long bridges required support from either piers or pontoons.[4]

A number of bridges were available by 1944 for D-Day, when production was accelerated. The US also licensed the design and started rapid construction for their own use. A Bailey Bridge constructed over the River Rhine at Rees, Germany, in 1945 by the Royal Canadian Engineers was named 'Blackfriars Bridge', and, at 558 m (1814 ft) including the ramps at each end, was then the longest Bailey bridge ever constructed.[26] In all, over 600 firms were involved in the making of over 200 miles of bridges composing of 500,000 tons, or 700,000 panels of bridging during the war. At least 2,500 Bailey bridges were built in Italy, and another 2,000 elsewhere.[13][15]

Field MarshalBernard Montgomery wrote in 1947:

Bailey Bridging made an immense contribution towards ending World War II. As far as my own operations were concerned, with the eighth Army in Italy and with the 21 Army Group in North West Europe, I could never have maintained the speed and tempo of forward movement without large supplies of Bailey Bridging.[27][28]

Post-war applications[edit]

The Skylark launch tower at Woomera was built up of Bailey bridge components.[29] In the years immediately following World War II, the Ontario Hydro-Electric Power Commission purchased huge amounts of war-surplus Bailey bridging from the Canadian War Assets Corporation. The commission used bridging in an office building.[30][31] Over 200,000 tons of bridging were used in a hydroelectric project.[32] The Ontario government was, several years after World War II, the largest holder of Bailey Bridging components. After Hurricane Hazel in 1954, some of the bridging was used to construct replacement bridges in the Toronto area.[33] The Old Finch Avenue Bailey Bridge, built by the 2nd Field Engineer Regiment, is the last still in use.[34]

The longest Bailey bridge was put into service in October 1975. This 788-metre (2,585 ft), two-lane bridge crossed the Derwent River at Hobart, Australia.[35] The Bailey bridge was in use until the reconstruction of the Tasman Bridge was completed on 8 October 1977.[36] Bailey bridges are in regular use throughout the world, particularly as a means of bridging in remote regions.[37] In 2018, the Indian Army erected three new footbridges at Elphinstone Road, a commuter railway station in Mumbai, and at Currey Road and Ambivli. These were erected quickly, in response to a stampede some months earlier, where 23 people died.[38] The United States Army Corps of Engineers uses Bailey Bridges in construction projects.[39] Two temporary bailey bridges are being used on the northern span of the Dufferin Street bridges in Toronto since 2014.

Army Mabey Johnson Bridge Manual Youtube

Gallery[edit]

US troops launching a Bailey bridge across a gap by hand

Bailey bridge over the River Arno, Florence, built on the piers of the original Ponte Santa Trinità (August 1944)

Barges being used to support Bailey bridging over the Seine at Mantes, France, August 1944

U.S. combat engineers slide stacked doubled sections of Bailey bridging into place at Wesel on the Rhine in Germany (c. 1945)

A Sherman tank and a Jeep ferried across the river Garigliano, central Italy, using a raft constructed from pontoons and a section of Bailey bridge (January 1944)

Bailey bridge built over bombed out bridge at base of Marienberg Fortress in Würzburg by the 119th Armored Engineer Battalion of the U.S. 12th Armored Division, April 1945

Bailey bridge over the Wadi el Kuf, Libya, with bridge sections used to construct the supports (2007)

Bailey bridge over the White Nile, Juba, South Sudan (2006)

Bailey bridge at Whitefish Falls, Ontario, Canada (2006)

Combat engineers inspect a bridge on Route Arnhem in Iraq (2009)

Construction of Baily bridge on 1970

Bailey bridge over the Coppename River at Bitagron, Suriname (1976)

See also[edit]

Mabey Johnson Bridge Manual

- Medium Girder Bridge a modern bridge of analogous use

- Pontoon bridge for another bridge type with mobile military application

References[edit]

- ^'The Story of the Bailey Bridge'. Mabey Bridge Ltd. Retrieved October 3, 2015.

- ^'UK Military Bridging – Equipment (The Bailey Bridge)'. ThinkDefence. January 8, 2012. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

- ^ ab'Launching the Bailey Bridge'. Tactical and Technical Trends (35). October 7, 1943. Retrieved 2011-09-11.

- ^ abc'How the Army's Amazing Bailey Bridge is Built'. The War Illustrated. 8 (198): 564. January 19, 1945. Retrieved 2011-09-11.

- ^ abServices, From Times Wire (1985-05-07). 'Sir Donald Bailey, WW II Engineer, Dies'. Los Angeles Times. ISSN0458-3035. Retrieved 2018-09-19.

He sketched the original design for the Bailey Bridge on the back of an envelope as he was being driven to a meeting of Royal Engineers to debate the failure of existing portable bridges

- ^Harpur 1991, p. 3.

- ^ abcJoshi 2008, p. 29.

- ^Harpur 1991, p. 4.

- ^Harpur 1991, p. 31.

- ^Harpur 1991, p. 37.

- ^ ab'BBC - WW2 People's War - The Sappers Story'. www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2018-09-19.

- ^ abHarpur 1991, p. 38-41.

- ^ abcJoshi 2008, p. 30.

- ^'Stanpit Marsh and Nature Reserve'. Hengistbury Head. Archived from the original on March 25, 2016. Retrieved 2011-09-27.

- ^ abHarpur 1991, pp. 48-50.

- ^Caney, Steven (2006). Steven Caney's Ultimate Building Book. Running Press. p. 188. ISBN978-0-7624-0409-4. Retrieved 2011-09-11.

- ^'Bridge Claim By General 'Used As Basis For Bailey Design''. The Times. 26 July 1955. p. 4 col E.

- ^Segerstrale, Ullica; Segerstråle, Ullica Christina Olofsdotter (2013-02-28). Nature's Oracle: The Life and Work of W.D.Hamilton. OUP Oxford. ISBN9780198607274.

- ^Harpur 1991, p. 113.

- ^Harpur 1991, p. 108.

- ^'No. 37407'. The London Gazette (Supplement). 1 January 1946. p. 2.

- ^Harpur 1991, p. 69.

- ^'Bailey Bridge'. Canadiansoldiers.com. 2010-11-27. Retrieved 2011-09-11.

- ^Harpur 1991, p. 87.

- ^Slim, William (1956). Defeat Into Victory. Cassell. p. 359. ISBN978-0-304-29114-4.

- ^'Blackfriars Bridge - Longest Bailey Bridge in the World'. Canadian Military Engineers Association. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- ^'Bailey Bridge'. Mabey Bridge and Shore. Archived from the original on 2007-06-15. Retrieved 2011-09-11.

- ^'Other Equipment Used By The 7th Armoured Division'. Btinternet.com. Archived from the original on August 13, 2010. Retrieved 2011-09-11.

- ^Massie, Harrie; Robins, M. O. (1986-02-27). History of British Space Science. Cambridge University Press. ISBN9780521307833.

- ^Magazines, Hearst (1948-05-01). Popular Mechanics. Hearst Magazines.

- ^Electric Light and Power. Winston, Incorporated. 1955.

- ^Harpur 1991, p. 106.

- ^Noonan, Larry (2016-10-11). 'STORIES FROM ROUGE PARK: Canadian military builds Baily Bridge to get traffic moving after Hurricane Hazel'. Toronto.com. Retrieved 2018-11-02.

- ^'Best of Toronto: Cityscape'. NOW Magazine. November 2007. Archived from the original on February 10, 2012.

- ^Journals and Printed Papers of the Parliament of Tasmania. Government Printer. 1977.

- ^'Feature Article - The Tasman bridge (Feature Article)'. Tasmanian Year Book, 2000. 2002-09-13. Retrieved 2018-11-02.

- ^'Twin Bailey bridges to fill the gap'. www.telegraphindia.com. Retrieved 2018-11-02.

- ^'Built by the Army, Elphinstone Road foot-overbridge inaugurated by a flower vendor'. The Times of India. 27 February 2018.

- ^Correspondent, Jennifer Solis. 'Officials focus on design of bridge over Artichoke Reservoir'. The Daily News of Newburyport. Retrieved 2018-11-02.

Bibliography[edit]

- Harpur, Brian (1991-01-01). A Bridge to Victory: The Untold Story of the Bailey Bridge. H.M. Stationery Office. ISBN9780117726505.

- Bailey bridge. Washington, D.C.: Department of the Army. 1972.

- Sanders, Gold V. (1944). 'Push-Over Bridges Built Like Magic from Interlocking Parts'. Popular Science. pp. 94–98.

- Joshi, MR (2008). Military Bridging(PDF). Defence Research & Development Organisation.

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bailey bridge. |

- US Army Field Manual FM5-277 Dated 9 May 1986.